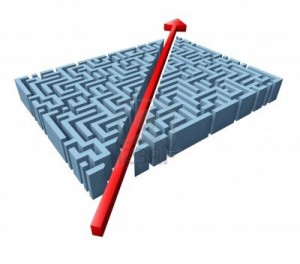

Shortcuts

By The Warden

Understanding the world around us requires a certain amount of basic assumptions. It’s these assumptions that allow our brains to perform repetitive functions automatically and leave our conscious minds free to focus on unique problems and solutions. They could be personal experiences (getting hit by a car really hurt, so let’s not run out in front of traffic), secondhand experiences (my buddy was killed in a car accident and since then I’ve learned the risks about passing at high speeds), or direct lessons (we watched a safe driving video in school). However we accumulate them, these assumptions make things easier.

Understanding the world around us requires a certain amount of basic assumptions. It’s these assumptions that allow our brains to perform repetitive functions automatically and leave our conscious minds free to focus on unique problems and solutions. They could be personal experiences (getting hit by a car really hurt, so let’s not run out in front of traffic), secondhand experiences (my buddy was killed in a car accident and since then I’ve learned the risks about passing at high speeds), or direct lessons (we watched a safe driving video in school). However we accumulate them, these assumptions make things easier.

The same concept applies in RPGs and it’s why explaining this style of gaming to newcomers can be a bit tricky. We all come into our fictional experiences with certain assumptions to ease the learning process, whether it’s character standards (knowing what to expect from a paladin or an elf), geography (we’ve all seen mountains and so have a good understanding of what scaling a mountain would entail), or mechanics (rolling higher is better). These assumptions – or shortcuts – speed up the learning time required for a new game and help players get straight to the point. They are the unconscious workings of every game and they depend on the work that came before us.

Creativity is an evolutionary process. Each generation obtains the work of their ancestors and processes their work into something further advanced, explored, and adapted; it’s the nature of all expressive forms, including art and science. Roleplaying games are no different. With every passing game captivating the public’s attention, other game designers find inspiration and adapt those works into something new. Steve Jobs once said, “Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things.”

This evolutionary process is what creates our shortcuts and it’s an important part of the design process. Why? Because knowing your shortcuts helps a designer focus on what matters, what will demand their attention over the coming months. (That’s right, you read that right. Months. If you’re lucky.) Knowing where your players will enter your world – meaning how much your players will unconsciously understand – sets the pace for the exceptions and variances you’ll want to consciously introduce. Say you’re looking to create a zombie survival game. Right away, you know the shortcuts to zombies: destroying the brain is the only way to kill them, they’re slow moving, and they flock together in mindless hordes of flesh-eating monsters. If you want to establish your zombies as quick and intelligent or let these suckers keep walking without a head, you have to introduce that into your game. Otherwise, if it walks like a zombie and eats like a zombie, it gets shot in the head like a zombie.

FANTASY VS. SCIENCE FICTION

Perhaps the two most popular genres in roleplaying today, each promises exciting possibilities and worlds impossible to experience in our lifetime. It’s imagination at its finest, revving like a finely tuned engine at the start of a race. Take it too far and you risk losing the audience’s attention and comprehension. Each genre has a certain number of baselines to establish and their own list of typical shortcuts to help players ease their way into the game. For example, fantasy assumes a basic level of engineering and technology from an alternate medieval era, hence the term “swords and sorcery.” As soon as your GM tells you it’s a fantasy game, you would have to be informed there are also guns. If the GM didn’t mention pistols or rifles or submachine guns as an option, you wouldn’t even consider it.

Fantasy’s shortcuts are based on the classics of the genre, primarily Tolkien’s stories of Middle-earth, to establish such assumptions of technology, race, transportation, and more. It was incredibly helpful to D&D‘s creators to use the elves, dwarves, and hobbits (and later change them to halflings for legal reasons) discovered in Tolkien’s novels as they were immensely popular and a huge inspiration for the game world. As fantasy evolves and new classics enter our realm of consciousness, these shortcuts adapt or increase in number to create new standards of expectation. If you’re running a brutal fantasy RPG, you could name drop “Game of Thrones” to explain the level of brutality in only three words. The number of times I’ve heard of an indie fantasy game as “inspired by the tales of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser” has gone beyond count and has received nods of support every time.

This tends to make fantasy’s shortcuts limited as the audience generally can not just be aware of these standards, but know them firsthand. It’s why I’ve been praying for a resurgence in excellent fantasy films since 2001 – to provide a wider acceptance of these standards and allow the genre to flourish under the spotlight. Science fiction doesn’t have that hurdle and works off assumptions of current technology and capacity. No one considered tales of travelling to the moon until the technology of the late 1800s made it possible to relate to these tales. If you thought of the moon as a deity, for example, would you take any story about men riding a rocket and finding aliens on its surface plausible or heretical?

Science fantasy combines the best of both worlds and allows fans of the genre’s classics – like Star Trek, Star Wars, Battlestar Galactica, Starship Troopers, and more – to gain an extra special secret handshake pass. Also known as geek cred, yet still allow non-fans to understand a basic expectation to keep up with the game. (All genres have their own secret handshakes, when you think about it, but I find science fantasy excels and thrives on it.) Tell a player they’re firing a laser pistol and they’ll understand it without question. Tell an uninitiated player they’re about to enter the Tardis and you’ll have to take a moment to break it down for them.

A FAMILIAR HACK

Game mechanics have their own shortcuts as well, with the most common and profound being the popular hack. Right now, for example, I’m reading Sixth World, a Dungeon World/Shadowrun hack. Why? Because as soon as I saw someone took the Shadowrun setting and applied it to Dungeon World rules, I was sold. I don’t know much about Shadowrun (it’s always been on my list and never had a chance to read anything for it), but I’m very familiar with Dungeon World’s rules. In this case, the mechanics were a shortcut for me to understand enough about the game and want to download it.

Mechanical shortcuts are not limited to the outright hacks, but to any game. Since inspiration comes from previous bodies of work, all game designers are inspired by a favourite game, even if it’s only certain elements. Recently I’ve been playtesting another designer’s work-in-progress inspired by the dice pool mechanic from Cortex Plus (and it’s because of the “work-in-progress” part that I’m not sharing any specific details, but stay tuned and I’m sure you’ll hear about it soon enough) and that’s exactly how the mechanics were introduced. “Has anyone played the new Marvel RPG?” Those of us who had knew exactly what to expect and simply needed to learn where this one varied.

Once again, these shortcuts are limited to the players’ exposure. If you’ve played Savage Worlds before and I tell you the dice explode, you’ll instantly know what that means and gameplay starts just a little bit sooner. If you’ve only played D&D before, the term will have to be explained and reminded until you have truly learned the new game. And those players will know exactly how to roll percentile without a d100 because it’s been a fundamental part of their game. Mechanical shortcuts are not always limited to rules, but tone and style. For example, a game introduced as a deep space exploration game built on Burning Wheel‘s mechanics may not strike a mechanical chord with a player because they’re yet to experience it, but if that same person has at least heard of it before, they can still gain an idea of the mechanics’ style from word of mouth and the game’s online presence.

Story games have truly blossomed since Fiasco and it’s become the go-to shortcut for other story game designers looking to attract an audience to their work-in-progress. Even game designers have become a kind of mechanical shortcut, as is the case with Pelgrane Press’ soon-to-release 13th Age, built with Jonathan Tweet and Rob Heinsoo at the helm. As part of the team behind the 3rd edition of D&D, fans have a shortcut of what to expect mechanically speaking and feel more comfortable trying out – or outright picking up – this new game. While this particular shortcut doesn’t exactly define the exact mechanics based on name alone (what I’m understanding about Numenera so far is that it’s different from Monte Cook’s earlier systems), but there is a comfort and trust level involved with this association and that’s exactly what a shortcut accomplishes. It allows us to bypass certain elements and get straight to appreciating and experience the work.

A NOD TO THE FOREFATHERS

As time rolls further and further into the future, shortcuts will come and shortcuts will go. They’ll change and they’ll remain the same. It’s what drives creativity and it’s an incredibly helpful tool not only for game designers, but consumers as well. When they know what to expect, they’ll be more inclined to purchase the designer’s work and keep the process ever moving forward. From those new games, new shortcuts grow and the circle of creation continues for another generation.

Pretty deep, huh?