The Perfect Fight (Part 5: Stand or Fall)

By The Warden

PREVIOUSLY: We have covered the first three-quarters of a combat management system’s key features. We’ve established a fight’s difficulty, built a timeline of how long the average fight should take, and provided the means for players to dish out the damage needed to bring the fight to an end. The final step can be the nail in the coffin or the thrilling cheer of victory: survivability. Because if none of the heroes are standing at the end of the fight, the game hits a bit of a bump. You can read the previous posts right here: Part 1: An Introduction, Part 2: Feeling the Rush, Part 3: Making It Last, and Part 4: A Necessary Pain.

PREVIOUSLY: We have covered the first three-quarters of a combat management system’s key features. We’ve established a fight’s difficulty, built a timeline of how long the average fight should take, and provided the means for players to dish out the damage needed to bring the fight to an end. The final step can be the nail in the coffin or the thrilling cheer of victory: survivability. Because if none of the heroes are standing at the end of the fight, the game hits a bit of a bump. You can read the previous posts right here: Part 1: An Introduction, Part 2: Feeling the Rush, Part 3: Making It Last, and Part 4: A Necessary Pain.

Here’s the catch with a game’s survivability: the Gamemaster is typically the one to take the fall if a fight ends up a TPK. I know the common rule is not to shoot the messenger, but most messengers don’t drag the corpse of bad news with them when the message is delivered. Unless your players are experienced and knowledgeable about game mechanics with enough clarity to spot major flaws before the final stroke fells the last hero, you’re going to get a lot of dirty looks.

It’s the fine line of survivability that makes the final impression of the game and its combat management in the eyes of players around the world. Too many deaths and the game becomes a grueling endeavour that will eventually turn off some players. No deaths at all and players will take unfair advantage of the situation and the drama of combat will be lost. By default, that leaves us with the perfect balance, but what exactly is the perfect balance? Is there really an issue with too many dead characters in every game?

DO WE NEED DEATH?

Personally, I like to see some mortality in my games as a player. I’ve experienced a lot of character deaths in my lifetime and get a rush of adrenaline when death hovers over my character or any other party member in a fight. Even if someone hovers close to 0 hp or drops to the ground and is later revived, it gives me that reminder of the risks involved. Particularly in a long standing campaign when hundreds of hours have been invested in a character. Sure, I can always make another character and join in the game, but I’ve grown an attachment to that first character and planned out a whole trilogy of novels based on his history. (Admit it, you have too.)

The possibility of dying in the campaign brings the threat and tension of combat when the players are safely tucked inside the warmth and comfort of modern living. In one-shots, death still plays a part because the reward is surviving until the end to provide that sense of accomplishment. Campaign deaths threaten to derail all our hard work invested in that single character and if we know there is a possibility our character can die in a fight, we tend to tread carefully.

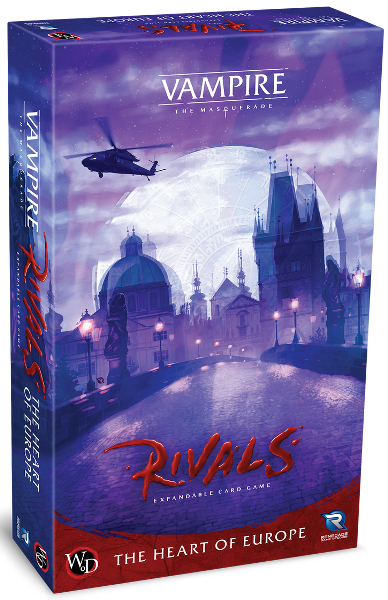

As a GM, I’m a big fan of ensuring my players’ characters are alive at the end to experience the conclusion and its corresponding rewards. Looking back, the last time I killed a character was back in 1994 when a human sidekick to one of the leads in our Vampire: The Masquerade campaign was riddled with bullets thanks to an impressive roll from myself. The player thought the scene was awesome and was happy to have his loyal companion die in a hail of bullets. Otherwise, I’m not sure if I’ve ever really killed a PC. Kind of a contradiction, isn’t it?

JUST THE RIGHT NUMBER OF BROKEN BONES

That contradiction exists in combat management because the primary goal of a fight’s survivability is to keep the players happy. A quick search through the comments section of any popular YouTube video teaches us the impossibility of such a venture, yet here we are nonetheless. If players last as long as a snowball on the BBQ, will they keep playing? Place that snowball in the freezer and you risk it growing in strength until it’s a giant block of ice that’s too heavy and awkward to throw without hurting someone.

This is where your combat system’s challenge comes into play. Is the fight supposed to be hard or realistic? Is it intended to be bloody and account for multiple character deaths? Then heroes should drop like stones. The Dungeon Crawl Classics RPG‘s character creation process has every player taking on multiple 0-level commoners into deadly dungeons; your final choice is based on who survives and gains that precious first level. Going back to Vampire for a moment, the opposite went down as characters could fall into a state of torpor from gunfire, but only temporarily. To truly kill a vampire, you need to go through an intense procedure, something that’s not going to happen by accident. For that game, if your character dies, your glare at the GM is mandatory.

Numerous tools are at your disposal to help characters endure the torments of war. Hit points and defence ratings being forefront, but it all depends on how your game has already been built. By manipulating and adjusting these values, you can work out a proper average for heroes to conclude a fight. If you want a bloody game, boost the hit points. Gritty and realism? You’ll likely want to ramp the defence.

Stop and think about the bigger picture. These heroes need to survive through more than just this fight; they have to reach the end of the adventure in some capacity, typically wounded and covered in scars. If they suffer terrible injuries in a single fight and have difficulty recovering from its effects before the next fight goes down, this could end up a major issue with your game. Survival extends to more than just the fight and that’s why it creates such a final and lasting impression for players. Dying in a single fight is one thing, but having the whole group wiped out because they were all dangling in with single digit hit points before the boss is crushing.

Many combat heavy RPGs adjust for this measure through a more creative strategy by categorizing enemies into ranks. Take a dungeon crawl, for example. You’re going to encounter a lot of resistance along the way, but the primary goal for the story is to reach the final villain in a grand confrontation. The heroes are expected to be there at the end with fewer resources to impose an increased challenge to the fight. Those resources are lost against minor opponents and a few strategically placed lieutenants (if you will) whose role is to smack the heroes around a little, but not intentionally kill them. By breaking these opponents into levels and design them to keep pace with character levels, Gamemasters can start the fight with some measure of assurance of the players’ survivability. Plus there’s the added benefit of “unlocking” new opponents as the campaign grows. You know you’re in the big leagues when it’s a pit fiend, yes, sir.

AHEM! EXPERIENCE, PLEASE

Surviving the fight is about more than continuation of the story and the sensation of victory in the face of imaginary danger. These characters fought really hard and put their lives on the line. They might be doing it for charity on behalf of those villagers, but they turn to the GM for a little something something. They want a reward for living through the fight.

And so we come right back to challenge. Campaigns are not about stagnancy, they exist to provide a rising story and game experience for players to enjoy. After a few games, they’ve already seen their character’s max out at dice rolls and experienced their abilities a few times. They’ll want to see something new to keep everything fresh and reward them for their dedication and quick thinking to the campaign. Rightfully so, they should be rewarded and part of that reward involves keeping up with the stronger characters over the course of the campaign.

This is the greatest task facing every RPG ever in existence and some of the largest and greatest publishers have struggled with it. By their own admission, Wizards of the Coast’s 4th edition of D&D stumbled and tripped over itself in the epic tier (levels 21-30) and allowed their heroes to become near unstoppable forces of good. This may have been fine for some, but it didn’t leave a comfortable taste for many others and many restarted new campaigns sticking to the first ten levels when it had the right balance for them. Many games have the same issues without ever having mechanical issues because it all stems from what keeps the individual group happy.

COMING UP NEXT…

Um, nope, that’s everything. Part 5 of a five-part series, remember?

In all honesty, this is a topic that could go on forever and ever, possibly as a column all its own to dive into the possibilities both mechanically and creatively for combat management. As a starting point, this is what I work with in my own designs before breaking down each step into rules and mechanics. How do you rank your steps?