Mechanical Morals?

By The Warden

Regardless of what you celebrate this time of year, the final month of our calendar is a time to reflect on the accomplishments and sins of the past eleven months. Whether you’re a child eager to convince Santa how good you’ve been all year or a full-grown adult setting down New Year’s resolutions with the goal of becoming a better person in the next, whatever you do and however you do it, our minds are centred on our morals.

Regardless of what you celebrate this time of year, the final month of our calendar is a time to reflect on the accomplishments and sins of the past eleven months. Whether you’re a child eager to convince Santa how good you’ve been all year or a full-grown adult setting down New Year’s resolutions with the goal of becoming a better person in the next, whatever you do and however you do it, our minds are centred on our morals.

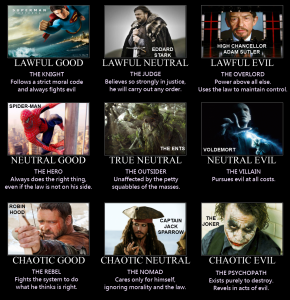

Morals are a huge part of our gaming experiences with some games taking more credit than others. I caught a tweet last week from Mike Mearls about D&D alignment. That word always catches my attention in gaming circles. Alignment. Actually, in all circles. It’s amazing how many words infer a gaming reaction when you see or hear them. That one may be my extreme example.

Anyhow, back to the tweet. Just prior to this week’s announcement of D&D next edition launching in the summer of 2014 [read that announcement here], its captain replied to a question about whether or not the new edition will feature spells such as protection from good or other more evil-aligned spells and goodies, including the ever-popular anti-paladin. The answer was a solid “no, but we’re saving it for a future release.”

Perfectly understanding as the flagship of the industry is clearly aiming for a broader audience, particularly the younger demographic, by pinpointing the core focus of the game: as valiant heroes braving dark dungeons against the forces of evil and horror. I’m totally on board with that as I’d love to get my nephew into roleplaying and he’s picked up this nasty habit of only wanting to play the good guy.

That’s not really my style. I’m a lawful neutral man. My characters live by their own code and my worlds are harsh and driven. Adventures I’ve created and written prefer to open the doors to all possibilities in every situation. Kill the prisoner who’s slowing the party down in their flight from a horde of orcs or drag him along and pray for a last minute solution? That kind of thing. I’ve always found the role of a fantasy hero walks the thin line between legendary figure and brigand. Think about it for a second. What would your party do if confronted by a tribe of goblins? Would you wipe them out and not think twice about the mass of bodies you and your fellow heroes have left behind? Or you can look at the absolute fact that heroes are always in it for the money. In my eyes, D&D heroes are mercenaries with good PR.

I like cutting to the chase and snipping out the illusion. Mercenaries, not heroes. They encounter the same dangers and benefits as heroes and in many cases deal with many other challenges uncommon in heroic adventures. It always surprises me how the description implies an evil campaign when other games hear about this, as if there can only be two ways to play your character. It used to bug me for quite some time and I often wondered if it was simply a case of stubborn tradition. Now I believe it to be something completely different.

It’s all in the writing. People play a band of heroes in D&D because the game is written to play a band heroes. That’s the soul of the game and as much tweaking and creativity goes into the game via new classes, alternate races, new feats, or entirely new tribute systems modelled after one version of the game or another, very few moral alterations exist of the game. What has always struck me was how wrong the soul of D&D was mechanically; it doesn’t fit at all. Take these three examples… um, for example.

- Initiative rolls are a very independent and random event in combat. Everyone rolls their own initiative and is assigned in whatever order exists out of their control. Other than delaying or readying an action, you have no control over how you can work together (save from any special benefits gained from feats or any means to alter a d20 roll). What you roll is what you get – very independent.

- The “heroes” collect XP for killing. Depending on which edition you play, they can also receive experience points for taking someone else’s treasure, stabbing someone in the back, or other felonious acts that could get you arrested in any civilized culture.

- This one may have been mentioned before, but it’s a big one in my eyes. Heroes get paid to save the world!! How many low-level adventures involve a desperate village scraping together enough coins to “thank” the heroes for killing the child-eating demon living at the bottom of their well?

Nothing about these three fundamentals of the game’s moral compass fits with the role of being heroes. Especially considering D&D’s original edition was modelled after the noble deeds of Tolkien’s books, but that viewpoint of character morality is dictated and locked onto by the game’s fluff text. Which is why I’m surprised evil is getting the boot from the upcoming core release, because the system doesn’t mechanically represent the fluff’s moral values.

But Warden, you might say, what about spells like protection from evil or magical healing abilities? Aren’t they an implied moral mechanic because they are restricted to those of a particular alignment? True, but is it inherent in the system’s core to the point that the game ceases to function or must be heavily modified if you’re looking to eliminate it? No, it’s not. In fact, with each new edition’s release, the importance of alignment has been subdued further and further until it’s nothing more than a character listing acting as a roleplaying guide.

As it stands, roleplaying morals are a fundamental guide to behaviour and characterization and just like morals, are abstract and interpretive. Mechanically speaking, they don’t exist. They can have an effect on the game and its consequences, but the game does not ride on them and that’s what truly makes these games so unique and interesting. When it comes down to it, the mechanics fuel gameplay, but do not define it. The game defines gameplay. How it’s written – not how it’s played – drives players and Gamemasters to take on the role of heroes, villains, and mercenaries. The rules are what allows everyone to play fair and work on the same page without butting heads and erupting into arguments during game time. Or at least try and keep them to a minimum.

It’s what allows each group to set their own moral compass and it’s something we might forget sometimes. There’s no one way to play any game, be it mechanically or spiritually, only the way you and your group enjoys their personal experience. While some games – earlier editions of D&D as the prime example – set down locked formulas for behaviours and viewpoints translating into alignments, there is always a level of interpretation to work with so long as you remember that alignments and morals are not a static definition. If they were, paladins would have been banned from joining any adventuring party a long time ago.