A Game of Turns

By The Warden

I used to go to the movies alone. It was during my early attempt at film studies in Toronto and I was filling time between classes (or skipping them when it became apparent this was not what I wanted for my life) by going to the movies. I was often alone. Everyone else had places to be and responsibilities or some crap. Many of my trips to the theatre were during early afternoon shows and there was barely anyone else in attendance. One of my best movie going experiences was watching The Crow with the entire 1,000-seat theatre all to myself. I must admit, I put my feet up.

I used to go to the movies alone. It was during my early attempt at film studies in Toronto and I was filling time between classes (or skipping them when it became apparent this was not what I wanted for my life) by going to the movies. I was often alone. Everyone else had places to be and responsibilities or some crap. Many of my trips to the theatre were during early afternoon shows and there was barely anyone else in attendance. One of my best movie going experiences was watching The Crow with the entire 1,000-seat theatre all to myself. I must admit, I put my feet up.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been roleplaying alone. No, I don’t mean gamebooks (though I have dabbled in that direction from time to time, including writing). I’ve been playing RPGs online while the rest of the party was comfortably seated around the table in an Ottawa basement. I live an hour away from the rest of the group and was unable to make the commute after an unfortunate case of explosion. To keep up with the exploits of our valiant heroes battling an oncoming Blood War spilling onto mortal soil, I had to use Skype and play remotely. For the past two-and-a-half years, I’ve been Shawn the webcam from the Full Frontal Nerdity comic strip.

There’s been an unexpected development playing remotely. I’ve found myself growing bored playing online. Not because of the GM, the story, or any of the hard work gone into the campaign at hand, but because of the mechanics. There’s a lot of waiting in our games, a lot of turns played out in order. And when you don’t have the luxury of chatting it up with your buddies around you as the GM handles combat resolution with Jimmy’s space marine, it’s a lot of staring and waiting patiently. You can’t chum it up with your friends the same way when you’re the only robot in the room. Think about it. I might as well have a voice box without volume control trying to whisper to my neighbouring player about the GM’s major BO problem. It can’t be done. Not to mention the difficulty in being heard in large groups, technical glitches, and the occasional GM who wants to see all your dice rolls (or will make them for you) tends to leave you wondering what it was about the game that attracted you to it in the first place.

What was happening was a shift in my attention. Like an observer looking down on an activity, I was able to see how everything flowed technically and with some distance and detachment from the story captivating the players attention. Similar to how someone in a helicopter would have a much better vantage on understanding what causes ground traffic to congest during rush hour. From my virtual perch, I could see the mechanical impact of our decisions and view the entire battlefield like Neo sees the Matrix. In short, I could see its 1’s and 0’s solely from this vantage point.

It was a revolutionary approach to my game design and has played a massive influence in my current work, so I have no regrets about learning Santa is actually Uncle Bill. If anything, I’m glad because now I know I can look forward to playing Santa. But this contention was the end of a long mental road of discovery and understanding how games are truly played (from my perspective, and there is so much more to learn). My conclusion was that my boredom was because all games, including RPGs, are dependent on the order of turns.

I dare say it was the determining factor in my shift away from D&D. The onslaught of monsters rushing through the canopy to attack came down to a strategic, round-by-round countdown of action and reaction. I knew the fight would last seven rounds and that I didn’t want to waste an encounter or daily power in the sixth round; any monsters not dead now will drop within the following round, if not sooner. Everything I did had no impact on the overall fight’s outcome because the game was designed to handle it. It didn’t matter how prepared and ready I was as the player, because my initiative roll was a 2 and I’m going dead last for the next half-hour. Nothing to worry about, the numbers have everything under control and you can try again in ten minutes. The barbarian will attack next, followed by the rogue, and the ogre squadron’s second unit will make the next move. Then after the fighter, wizard, and goblin bow warriors will it be yours again. Nice and neat.

This train of thought really bothered me. Without the social camaraderie of fellow players, are these games truly nothing more than a complex board game of turns? Well… yes. There’s no doubt that the foundation of a game is to simulate another activity with abstract rules and guidelines to keep things running smoothly and enjoyably. When we taught how to play together as kids, we were taught to wait our turn. Everyone would have a chance to play and by working together, we’ll have a lot of fun. A roleplaying game is a complex extension of that principle, but it’s still using the same principle. It’s a game of turns.

THE MECHANICAL ADVANTAGE

So what’s the big deal, right? It’s a game, it uses turns. It’s asking an awful lot to build a game where everyone just stumbles over each other and the first one to be heard over the cacophony of descriptions and dice rolls gets to go first. It makes sense to use turns, but what it is about the concept that’s standing out? It’s been bothering me for months and I think it’s clicking.

It’s the fact that I’m thinking about the mechanics while I’m playing instead of focusing on playing the game with the mechanics in hand. It’s the same explanation behind dropping out of film school close to twenty years ago (yipes!). The business of film was getting in the way of my enjoyment of film. Even today and despite my out-of-date knowledge of film technology and process, I find it difficult to watch the majority of films without an awareness of a director and crew standing behind the camera, framing, lighting, sound, everything. Those few times I’ve been able to watch a movie and truly loose myself in the moment were magical events and I haven’t had one of those with D&D as I did in bygone years.

Is the fault of my brain and its screwy wiring or the game itself? Is it set up in a way that the mechanics have taken precedence over the concept? (This is the opposite intention of concept and mechanics, as we talked about last week in The Canadian Principle.)

Maybe a bit of both, but there does seem to exist a propensity for RPGs with large character options and complex mechanics to require an understanding of the mechanics to maximize your character’s output. For example, how many times have you chosen a feat, power, spell, or other character option in a game and found yourself completely disappointed by its performance in the game?

I ran into this with the 4e barbarian and my expectations of its ass-kickery. The Rampage class feature allows a barbarian to make an additional melee attack if you roll a critical hit. Awesome, right? During play, it hardly came up and it wasn’t until I realized the frequency of attack rolls versus the frequency of a natural 20 (because my best weapon had a poor critical range) made the Rampage feature at best a random daily power. The same applied to my miscalculation of how frequently temporary hit points came to the barbarian. You don’t actually drop a lot of enemies in D&D, you do a lot of damage until someone gets lucky and delivers the killing blow. It doesn’t happen every round.

This is not a complaint at the mechanics of the barbarian by any means, but an example of how aware of the game’s mechanics plays a role in how you play the character. If you play a game for the first time and were told your character could make an extra attack roll every round, you’d be excited to try it out. When you find out that extra attack only happens whenever you cause at least 20+ damage, it changes your excitement level. Experienced players with a firm grasp on the mechanics and how they affect powers and abilities gain a solid advantage in game play and are rewarded for their knowledge with the ability to assemble truly awesome characters.

A SIGN OF GROWTH

Comprehending a game’s mechanics is essential to any game play and those with a firmer grasp of how they affect your options will always have an advantage in character design and growth. It’s no different than someone with innate skills of engineering and engine repair would have to fix a car over someone who’s learning how to change the oil for the first time. Where does the line between “no experience required” and “experience an asset” exist in game play and what are the advantages to either style?

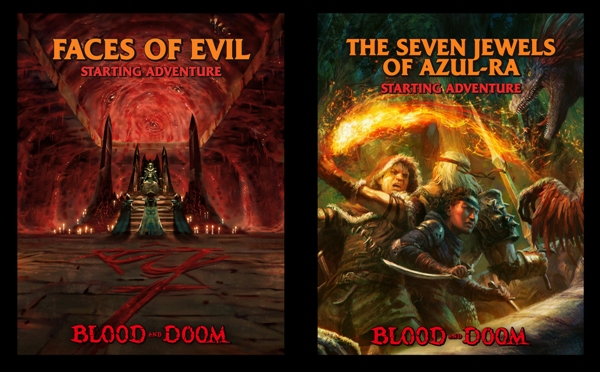

Quick-play editions and previews designed for conventions and one-shot tryouts are perfect for systems with little explanation and experience required. Everyone starts off with equal footing because it’s designed to entertain those who have never tried it before. You can experience it as an introductory story or as an introduction to new mechanics on equal footing and develop your own experiences as a group because that’s the goal of these games: to give you an immediate and lasting experience.

Campaigns and experienced players are a perfect combination, let’s admit it. To keep up with the game’s challenge across weeks, months, or years of play, players need to be as challenged as their characters. Unlocking new abilities and pushing the limits of possibility higher and higher as your story ascends closer and closer to the dramatic conclusion is the roaring fireplace to a good book. Elongated stories, including campaigns, develop attachments to their characters by watching them grow and evolve in these difficult times to become better, more relatable people. Accessing the game’s mechanics and learning how to use them to your advantage is another measurement of growth and progression.

A FATEFUL CHOICE

And so I return to my initial conundrum. If I feel this way about the game that’s been such a huge part of my gaming life, should I continue to play? Am I failing to experience it as it was intended? Or perhaps I can experience the game from a different point of view? What better way to truly gain a foothold on the next edition than to study it like a hunter’s prey? Because someday, I will step over the crest of an overlooking hill as my cohorts rise from a night’s slumber and rejoin my fellows in battle. When that fateful day comes, I should return wiser. What better way to make that happen?

Hmm…

Someone get my broadsword.