Representation and Simulation

By The Warden

The beauty of PDF publishing is the cheaper alternative to dead tree copies (for those who price their PDFs appropriately – many publishers will only dock a couple of bucks from the dead tree price). Take for instance the Legend RPG released by Mongoose this month. As we all know, it’s Runequest II with a new name after going through legal loopholes, but the rebranding has created an unexpected boom in Legend’s sales. I’ve never read a Runequest book or even flipped through its pages, but a complete fantasy system tagged at $1 was too good to pass up.

For those previously uninterested, Legend uses percentile dice as its core mechanic. All dice rolls are made from a wide selection of skills built from the combination or multiplication of assorted characteristics simply by rolling within your skill’s percentile chance with modifications based on the individual challenge attempted. It’s a very old-school technique – what you see on your character is what you roll for – and these mechanics got me thinking to the history of RPG mechanics at its simplest.

For those previously uninterested, Legend uses percentile dice as its core mechanic. All dice rolls are made from a wide selection of skills built from the combination or multiplication of assorted characteristics simply by rolling within your skill’s percentile chance with modifications based on the individual challenge attempted. It’s a very old-school technique – what you see on your character is what you roll for – and these mechanics got me thinking to the history of RPG mechanics at its simplest.

REPRESENTATION: WHAT YOU SEE IS WHAT YOU GET

In the beginning, TSR said “Let there be dice.” And it was beautiful. Characters were built into a small stack of six ability scores ranging from 3 to 18. From there, THAC0 (To Hit AC 0) was born to determine whether your character could strike an enemy and inflict damage. The process was a direct translation of what appeared on your character sheet; if a monster’s AC was 7, you needed to roll a 14 to hit it. Your character sheet told you exactly what was needed to accomplish your desired task, a process I like to call “representation.”

The majority of early RPGs featured this mechanical style and it continues today through many “old-school” RPGs (i.e. Labyrinth Lord, Dungeon Crawl Classics RPG) and independent games. Each player is able to assert the result of his or her dice roll by the stats written on their character sheet. Want to lift something over your head? Look at your Strength and roll that number or less on a d20. Representation mechanics are incredibly dice-friendly too; the higher your stat number, the more practical every number of your dice becomes. A Charisma of 18 means every number save for 19 and 20 becomes your best friend. Gamemasters can modify the situation, but the generic chance of success was right there in your handwriting.

A monster’s AC was the largest modifier in the game. Tougher creatures sported a lower AC, requiring your THAC0 (and therefore, your level) to increase before you had a fighting chance on killing the bastard. Hence the THAC0 bar found on every character sheet told the player exactly what number they needed to roll for that ultimate success. Quick, simple, effective.

SIMULATION: ALL THE THRILLS, NONE OF THE BODILY HARM

In time, our games began to expand in complexity. Unique skill systems allowed you to create a wider ranged of individuality in characters rather than relying solely on classes and categories of character creation; with those skills came versatility in both character and adventure. Our characters could now exceed in climbing, acrobatics, book knowledge, and wilderness survival through choice rather than generic assumption, allowing Gamemasters opportunities to mix and match the challenges we faced. Doing so meant the core mechanics had to adapt with these skill subsets and so “simulation” mechanics were developed.

Simulation mechanics translate the basic statistics of your character into modifiers, a number of dice, or other techniques applicable to the resolution mechanic of the game, which are then pitted against a target number to determine success. This method allowed Gamemasters (and designers) a wide variety of tools to beef up their challenges so long as players could apply these modifiers and gain additional modifiers based on individual abilities, environmental factors, and more. This process presented your character’s abilities, but not their chance of success, and built a near empire of player supplements for new modifiers stacked with those core elements assembled during character creation. Having a hard time swimming? It was easy to find a way to improve your chances without having to make life-altering decisions.

What simulators made up for in complexity required a sacrifice in pacing. Blogs abound with suggestions for how to speed up spellcasting, combat rounds, even character creation. Many of these “revisions” are compounding optional rules, adding even more material for your game. These games are loaded with charts and tables for each application; the Earthdawn RPG uses “steps” to determine how many dice you can roll for each individual action, meaning you have to have a chart listed with your character sheet for tracking how many dice you roll every time. In theory, all this additional effort seems counter-intuitive to the definition of roleplaying games, yet the top five sellers listed every quarter show simulators at the top of the pile.

What simulators made up for in complexity required a sacrifice in pacing. Blogs abound with suggestions for how to speed up spellcasting, combat rounds, even character creation. Many of these “revisions” are compounding optional rules, adding even more material for your game. These games are loaded with charts and tables for each application; the Earthdawn RPG uses “steps” to determine how many dice you can roll for each individual action, meaning you have to have a chart listed with your character sheet for tracking how many dice you roll every time. In theory, all this additional effort seems counter-intuitive to the definition of roleplaying games, yet the top five sellers listed every quarter show simulators at the top of the pile.

SO WHAT?

It’s a very good question. So what? The games still play with the same objective, right? Yes, but this one adaptation has lead to significant changes in how our RPGs are produced and marketed. More importantly, they’ve lead to a major shift in how players and Gamemasters control the flow of the game.

Representation places control of each character’s actions squarely in the hand of the player. What are your odds of hitting your enemy? It’s right there on your character sheet. Once your dice comes to a stop at the edge of the table, you know exactly how well your character did their job. Using Legend’s mechanics, a character with a 70% chance of making the jump across the chasm will know as soon as they roll 70% or less. The player can proclaim their success or failure without further consultation from the GM and this is one of the main draws for many independent RPGs looking to create dynamic group interactions. These games focus on players telling the GM what they’re going to do rather than asking if it can be done. For example, whenever Fraser Ronald from Sword’s Edge Publishing runs Sword Noir, the motto is always “You tell me what you want to do and how you want to do it, then roll to see if you do it.” With all target numbers of the game listed on their character sheet, players will know instantly if their roll was worth the effort.

It’s a perfect fit for the smaller budget of independent publishers, particularly those who flourish on DriveThruRPG. Ten bucks gives you everything you need within 50-100 pages, especially since there’ll only be a few supplements ever released within the next five years. Representation games only need to demonstrate the basics and instantly provide hours of amusement with little fuss or explanation.

Simulation’s difficulty remains in the hands of the Gamemaster, no matter how you look at it. Either the target number you need to roll remains a secret with the Gamemaster or all players are immediately told the target required, but this target adapts to each situation. Simulation games typically contain numerous charts featuring calculated formulas for determining target numbers based on each challenge’s factors. The guidelines for determining the target number on swimming are different from climbing because each challenge faces its own issues; you never have to climb against a current and swimming has little to do with gravity. Even memorizing the entire book only tells a player of typical target numbers; there’s nothing stopping a GM from modifying those numbers even further to keep players on their toes. In a simulation, the onus lies on the player to do their best to prepare for as many situations as possible and hope for the best when the time comes.

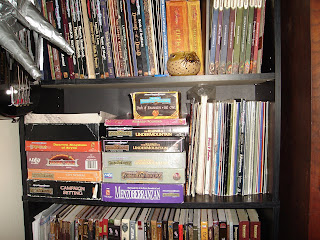

For the big publishers, this has lead to a huge shift in the market: player supplements. Used to be only the GM needed to fork over the money for more products, but the innumerable options for players have lead to more than half the shelves stacked high with character support products, followed by adventures and campaign sagas close behind. And for those games providing an open license for third-party publishers, more goodies could be made available without taking the financial risks directly. Take a look at your d20 collection; how many adventures do you have compared to supplements?

For the big publishers, this has lead to a huge shift in the market: player supplements. Used to be only the GM needed to fork over the money for more products, but the innumerable options for players have lead to more than half the shelves stacked high with character support products, followed by adventures and campaign sagas close behind. And for those games providing an open license for third-party publishers, more goodies could be made available without taking the financial risks directly. Take a look at your d20 collection; how many adventures do you have compared to supplements?

For me, people are afraid they’re “playing it wrong” and it’s a very unusual reaction. We all know there is no “wrong way” to play our games so long as we’re enjoying them, but it permeates the game nonetheless. I’m just as guilty of it as everyone and constantly have to remind myself that my players won’t know (or care) if it’s broke if they’re shouting for joy at killing the dragon which should have incinerated them.

DELIVERING YOUR GAME

This column is all about the translation of RPG mechanics by players and GMs alike. Representation and simulation mechanics each have their strengths and flaws and either method speaks to each individual differently. Like any good mechanic, there’s always room for individual modifications and presentations so there’s never truly one way to play the game. That being said, how much of an impact does either method deliver to your game?

Representation mechanics are simple and generally effective without getting into incredible detail on how your character performs each task. Yet, this simplicity eventually became a drawback to a large number of players. I remember a huge debate on whether or not my AD&D druid could ride a horse because he didn’t have the non-weapon proficiency. What? Those who adore this style of mechanic are the right type of player/host – they don’t need the game to tell them every single detail, just a resolution mechanic for determining if an action works or not. These games typically require only one book – the core book – and flow seamlessly for countless hours of entertainment. Climb checks? Nah, just roll your Strength. These games are built on a principle of heroic favor. It’s assumed your character is awesome, you just need the dice to prove it with a chance for the occasional failure for balance.

Simulators fill a need amongst many gamers for detail and accuracy. It’s a rather bizarre concept that nearly all of the most popular games in the field are simulators with hours spent on character creation, hundreds of pages on individual subsets, categories, spells, weapon classifications, and more are marketed to new players. D&D Essentials and the Pathfinder Beginner’s Box are recent versions presenting “cleaner” versions of their original rules, but this practice has been in place for decades. Creating the perfect simulation in a roleplaying mechanic has become the quest for the Holy Grail and lead to countless amounts of errata and online debates on the accuracy of rules. Flip through a copy of Mutants and Masterminds to see what I’m talking about.

It seems these styles and their chosen audiences are backwards, doesn’t it? Shouldn’t new players turn towards the more abstract representation games to get a handle on the basics of roleplaying games before expanding into the mind-blowing page counts of simulators? Or does a good GM need to understand the elements of a game through a series of complex rules before gaining the confidence and experience to run a more abstract representation game? Backwards though this may be, it’s not surprising considering human behavior.

Let’s look at sports. Every popular league has a giant rulebook detailing the do’s and do-not-do’s for every possible play and outcome in the game, hiring full-time referees to monitor every game, even calling on up-to-date technology such as instant replay to ensure the most accurate translation of the rules applies. And every season, rules are changed to suit recent trends and viewpoints amongst owners, players, and fans of the game. Billions of dollars say they’re doing something right. Yet, on streets and backyards across the world, kids play a simple game of touch football, ball hockey, or a friendly round of 21 without the word “penalty” ever spoken. It’s human nature for us to view excellence as complex and this concept has shifted into our roleplaying games.

IN CONCLUSION

Try as we might, the debate continues on how to present our games. Monte Cook’s Legends & Lore column addressed this very issue recently.

“Since the launch of (Dungeons & Dragons) 3rd edition and continuing on into 4th edition, the game has focused more on providing rules directly and overtly. This approach also made it easier to adjudicate situations that the rules didn’t cover explicitly. Prior to 3rd edition, however, “the DM decides” wasn’t just a fallback position; it often was the rule. This sometimes cultivated the perception that if a DM makes a call that goes contrary to the rules then he’s doing something wrong. And of course, there’s a tendency for rules-lawyer players to challenge or at least question such rulings…

“Empowering DMs from the start facilitates simulation. No set of rules can cover every situation, and the DM can address fine details in a way no rulebook can. When it comes to how much of your turn is spent opening a door, perhaps it depends on the door. A large, heavy metal door might be your action to open, while opening a simple wooden door might not be an action at all. Another door might fall in between. Do you want the rules to try to cover every aspect of this relatively insignificant situation?…

“DMs need to be able to run the game, but is their right to override the rules “Plan B” or “Plan A”? Is DM adjudication breaking the rules, or is it in fact the rule itself?”

– Monte Cook, Legends & Lore column, December 6/2011

When it’s all said and done, there’s only one right way to play your game: the fun way. I’m up for either, depending on the individual running it. My Pathfinder monk has learned to become the deadliest killer in the Seven Realms by mastering the skills of a rogue, moving in at his top speed to add massive sneak attack damage and preventing opponents from making attacks of opportunity whenever they are struck with these devastating attacks. Meanwhile, I have a blind archer in Kiss My Axe who can fire off unlimited shots without penalty simply because it’s just really frickin’ cool. Strategy and imagination each have their own role in the worlds we create, yet exist on their own. It’s the age-old adage we read in the introduction of every game ever purchased: it’s your game. Play it the way you want and have fun.

MORE!!

Ars Magica, 5th Edition: I had no idea until reading about the latest edition to the ultimate magic system in roleplaying that Jonathan Tweet (D&D 3rd Edition) AND Mark Rein-Hagen (World of Darkness) were behind the original. The alternate history world of magic returns in updated fashion and promises to streamline your spells more than ever.